Becoming a Parent abroad

“Men and women are not only themselves; they are also the region in which they were born, the city apartment or the farm in which they learnt to walk, the games they played as children, the tales they overheard, the food they ate, the schools they attended, the sports they followed, the poets they read and the God they believed in”

(W. Somerset Maugham. The Razor’s Edge)

Living abroad, away from our way of doing things, our family and our support network is difficult as it is. Now imagine adding to that equation becoming a parent.

Parenthood goes beyond the biological processes of reproduction, encompassing traditions, rituals, cultures and beliefs. It is a cultural and social process and when we are faced with new values, behaviours and parenting practices that we know nothing about it can make us start questioning everything we knew about being a (good) parent. As immigrant parents, in addition to everything related to parenthood, we have the extra burden to learn and adapt to the new cultural norms that we encounter.

Why does it matter?

As Michael Tomasello explains we are cultural beings and group-minded individuals. It means that we have created conventions, norms, institutions and way of doing things built on cultural common grounds.

Culture plays an essential role in how children see, interpret and understand the world. Parents of each generation have the important task to introduce their children to the codes, values, norms and dynamics of their surrounding culture. This process is called socialisation and it is a central process of personality formation for all children. Immigrant parents must do exactly that but in a non-native and non-familiar environment. In this context and in addition to the common parenting obligations and challenges, immigrant parents need to find a balance between the desire to retain their values, beliefs and cultural heritage, and the importance of integrating and participating in the host culture.

This process is called acculturation: the changes that we undergo as a result of contact with a culture not our own. On the other hand, enculturation is the process of learning our own culture.

Immigration requires acculturation which involves processes of change. It is not necessarily a confrontation or a clash of civilisations (even if it can turn into one).

Not all individuals cope with acculturation in the same manner. The psychologist John W. Berry’s explains this process in his fourfold model:

- Separations: Individuals affiliate exclusively with their culture of origin.

- Assimilation: Individuals affiliate only with members of the host culture.

- Integration: Individuals affiliate with members of both cultures.

- Marginalization: Individuals affiliate with neither culture.

Immigration and acculturation can have a strong impact on families. They can affect and sometimes destabilise the parent-child relationships and can even be sources of tension, conflict or distress. Finding a healthy balance leads to the most positive adaptation and to psychological well-being.

For the processes to be smooth it is important that parents, educators and all agents of socialisation understand that :

- Integration needs to be a two-way process (involving many cultures) where individuals of different cultures change as they meet one another.

- Acculturation that isolates the child from his or her own cultural heritage may be detrimental, because a healthy cultural identity is essential to both educational and social developments.

Winners begin early:

Diversity and Inclusion in early years

As immigrant parents or as people working with children from many backgrounds, it is essential that we understand that all children need to develop a healthy and positive sense of self-identity.

In the first years of life, the first circle i.e. the family needs to provide a sense of positiveness about their origin, language, nationality, skin colour… BUT ALSO show and work on their acculturation and integration effort. The attitude of parents towards the “new culture” has a direct influence on the children and is crucial to the development of their self-esteem, confidence and sense of belonging.

Social identities formation starts in the family and are cultivated and flourish at school.

In reality, the process of forming an identity begins at birth. Early childhood is a significant period for the children’s development including the emergence and the development of their language and physical abilities as well as their psychological, emotional, cognitive and social skills. The home and educational environments in which children evolve in the first years of their lives will have a great influence on the stability of their mental health, their emotional security as well as their cultural and personal identity.

At school, children develop a sense of who they are from the relationships they form and from all the messages they receive from different supports and resources (books, television, magazines, computer games, music…). They not only become more aware of how they are perceived by others but also how others view the people who belong to the same group as them.

Children who regularly see people who look like themselves represented positively and in high positions, gain confidence and a sense of possibility. When children are constantly bombarded with images portraying people from the same background negatively, they develop a negative image of who they are. Similarly, those who see that what they do at home is never mentioned may start to feel “weird” and express concerns about being different.

Educational institutions have a role to play in making sure everyone is included and represented by exposing children to as much diversity as possible but also starting and encouraging discussions and dialogue about all diversity and inclusion topics (diversity and inclusion blogpost here). Diverse and inclusive early childhood program can foster and develop all children’s creativity, self- esteem, empathy, cognitive and critical skills…

Those who are exposed to diversity and grow up in a diverse environment, know there is diversity in how people look, talk, behave and that these variations are normal. Diversity equips them for a global world. Those who spend their early years in homogenous settings will associate what is normal to a particular skin colour, language… and might develop negative feelings towards what is “unusual” for them. Furthermore, less diverse environments also usually mean fewer conversations about diversity and, in turn, provide more room for prejudice.

All children deserve a diverse, inclusive and rich environment where they are positively represented and where they can learn with other children and from their surroundings.

What do you think?

References

- Cole M, Hakkarainen P, Bredikyte M. Culture and Early Childhood Learning. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/culture/according-experts/culture-and-early-childhood-learning. Published February 2010.

- Cole M. Cultural psychology. A once and future discipline. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1996.

- A Natural History of Human Thinking. Michael Tomasello. Harvard University Press, 2014. 192 pp., illus.

- Mesoudi A (2019) Correction: Migration, acculturation, and the maintenance of between-group cultural variation. PLOS ONE 14(4): e0216316.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216316

- Bornstein MH, Tal J, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Parenting in cross-cultural perspective: The United States, France, and Japan. In: Bornstein MH, ed. Cultural approaches to parenting. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991:69-90.

- Greenfield P. Weaving generations together: Evolving creativity in the Maya of Chiapas. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press; 2004.

- John W Berry 1997, Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Applied Psychology: An international review 1997 46(2), 5-68.

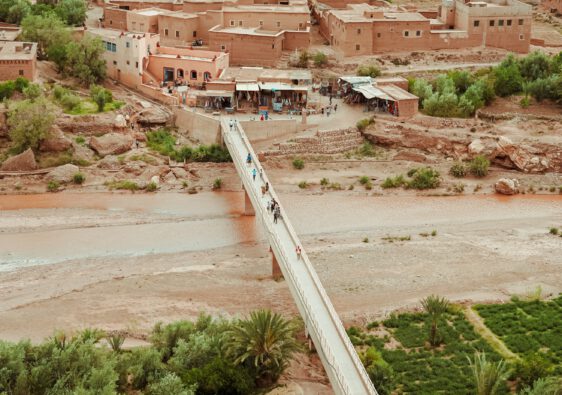

Photo by Julian Hochgesang on Unsplash5